I Beg To Differ

Like Beads on a String: The Master

Posted by Jennine Lanouette on Wednesday, October 17th, 2012

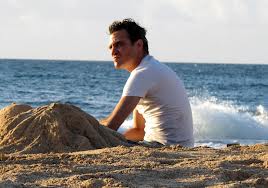

The opening images of The Master gave me a visual thrill – blue swirling water in a ship’s wake, a sailor chopping into a coconut, making love to a woman made of sand, drinking from a torpedo shell, passed out on a high perch. It was clear to me that writer/director Paul Thomas Anderson was out to challenge narrative convention. I was eager to see what was to come.

thrill – blue swirling water in a ship’s wake, a sailor chopping into a coconut, making love to a woman made of sand, drinking from a torpedo shell, passed out on a high perch. It was clear to me that writer/director Paul Thomas Anderson was out to challenge narrative convention. I was eager to see what was to come.

But by 20 minutes in, I was bored. I wanted to go with Anderson wherever he was going, but there was no denying the story had not engaged me. Looking around online afterwards, I was relieved to see that I was not the only one. Others were admitting they were bored, too.

Of course, when it comes to challenging films, there’s boring . . . and then there’s boring. The first I would characterize as the putting-in-time-for-a-payoff kind of boring. These are the films that build slowly, deliberately, incrementally towards a subtle yet profound ending. Or, if no such immediate pay off occurs, they stay with you for hours, even days, paying off in more and more layers of meaning emerging out of idle reflection. These are the rare good kind of boring, for which you simply have to concentrate a little harder to get the reward.

The second kind of boring is the more common one – an experience that offers little to no gratification, either immediate or delayed. One can write off such a film as poorly executed, or just chalk it up to personal tastes. But with a film that is clearly designed to push the bounds of cinematic storytelling, I prefer to think that boredom without payoff indicates a narrative experiment that didn’t completely work out.

The next morning I went to see it again, mostly to see if there was a payoff I had missed. But also to look more closely at the elements of Anderson’s narrative experiment. I noticed two things: 1) a prioritizing of visuals and dialogue over action, and 2) a downplaying of cause and effect relationships between dramatic events.

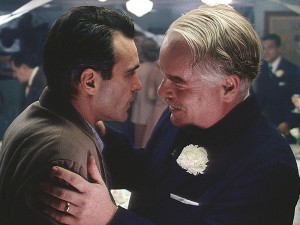

Film is, indeed, a visual medium, but it is also time-based, allowing for action and dialogue. These days, of those three, we often see action getting prioritized, which may be why Anderson made his choice to go with the other two. (By action, I mean: What are the characters doing? What are they doing to each other?) What sparse action Anderson does allow seems to center around the drifter, loner, World War II veteran Freddy (Joaquin Phoenix) manufacturing rotgut, passing out drunk or going ballistic. Otherwise, the film has long sequences of Freddy either wandering around aimlessly or hanging out in the background, while, in the foreground we see or hear the Master (Phillip Seymour Hoffman) and his disciples espousing unorthodox philosophies. True, the “processing” sequences could be considered action (the Master is manipulating Freddy), but the heavy reliance on repetitive dialogue puts them at the very low end of the action scale.

Cause and effect is a dramatic technique that gives a story momentum. Without it, a film is describing a chronicle of events, one following another, like beads on a string – this happens, then that happens, then that happens, then that happens. With it, one event leads to another, like billiard balls on a pool table – this happens, which makes that happen, which makes this next thing happens, which leads to this other thing happening. This action/reaction creates relationships between events and gives energy to their progression, like the balls shooting off in all directions. But in this film there just isn’t much of it and when it is there, it’s put in the background, as if Anderson doesn’t want to depend on it to move his story along.

For example, there is a scene in which the Master is demonstrating his past life, time travel methods at a gathering in the home of a New York socialite, and he is mildly confronted about his philosophies by an onlooker. Three scenes later, his group has relocated itself to Philadelphia where they are welcomed into the home of another well-to-do lady. But it’s not for another five or six scenes that we learn that the New York socialite is taking legal action against him for misuse of her foundation’s funds. We can surmise then that he was actually chased out of New York, which may or may not have been prompted by the conflict with the onlooker. But we are never shown the Master in direct conflict with the socialite, so, while the cause and effect relationship is there, it is not put in the foreground to move the story forward. Thus, the film is structured more as a chronicle of events than a dramatic unfolding.

A third thing I noticed after my second viewing is that the sympathetic character function is given a very light touch. This is usually the first thing I look at when finding myself not fully engaged in a story. Am I on board with the main character? In other words, do I care? I don’t mean “care” in a sentimental way, like he’s a Teddy Bear I want to hug. I mean “care” as in, Do I have any interest in what happens to him? Or could he go jump off a cliff for all I care? If I don’t care what happens to him, I’m less likely to be interested in his story. To fulfill the sympathetic character function, there is usually a moment very near the beginning that shows the character at some kind of power disadvantage, which is to say, as an underdog. For some reason, far be it from me to explain, the human psyche can’t help but become attached to an underdog.

Freddy, of course, has much to qualify him as an underdog. He’s a traumatized war veteran with an alcoholic father and mentally ill mother. Should be a slamdunk for creating viewer sympathy. But these details of his life are given to us through visuals and dialogue only. We see him on a ship in his sailor uniform, we hear a speech given to him and his comrades about their “nervous condition” and we see and hear him being put through a psychiatric exam. What we don’t see is the action of him actually being traumatized, the battle scenes, the narrow escapes, the blood and death all around him. Granted, this battle-scene approach, while proven to be effective, is a bit heavy handed. And there is certainly nothing wrong with taking a lighter approach, except that it runs the risk of not engaging viewers sufficiently to sustain them through the story (without getting bored).

The consistent thread here is not relying on action as the primary mode of communication, which is an interesting experiment. The downside is there is a perceptual function to action. It helps us absorb information. Through action, meaning goes straight into our unconscious. If we were to see Freddy cowering in a ditch with bombs exploding overhead, we would unconsciously absorb the information that he is traumatized. When, several scenes later, we see him, in civilian life, picking a fight, losing control and smashing things, we would know the psychological context for that behavior. We wouldn’t have to think about it. What this film did instead was report to us through dialogue that Freddy has a “nervous condition,” requiring us to put conscious effort into attributing his volatile behavior to his combat experiences. Similarly, without directly seeing the Master arguing with the New York socialite, the viewer has to consciously connect the dots to integrate the fact that he had to leave New York because of that conflict.

So what’s the problem with making the viewer think? It interrupts the illusion that we are witnessing real events. One of the cardinal rules of conventional filmmaking is to avoid at all costs breaking the viewer’s “suspension of disbelief.” This is why you make sure not to have the microphone in the shot. You don’t want the viewer to lose their absorption in the story by thinking, “What’s that microphone doing there?” This is also why you build in cause and effect relationships to move your story forward, so the viewer doesn’t have to think, “What’s that scene doing there?” The traditional view is that if you want to maintain the suspension of disbelief, you need to make sure the viewer is never pulled out of the story to think about what’s going on.

But there is another school of thought that says taking your viewer down a path of mindless absorption is an insult to their intelligence. These are the writers and directors, such as Paul Thomas Anderson, who want to challenge viewers with non-conventional techniques, to pull them out of unconscious absorption and make them think.

However, I must point out, there’s thinking . . . and then there’s thinking. On the one hand, there’s confounding your viewer with narrative dots to connect (Huh?), jolting your viewer with images of middle-aged naked ladies at a dance party (What?), and keeping your viewer at a cool distance by reporting, rather than showing, the main character’s traumatizing past ((yawn)).

Then, on the other hand, there’s giving your viewer something to think about, which brings us back to the matter of payoff. Much of the anticipation for this film was around advanced word that Anderson was taking on L. Ron Hubbard and the origins of Scientology. The audaciousness of the undertaking was impressive. And Anderson, not a withering presence, seemed well suited for the task. Many looked forward to an expose, a critique or at least some kind of exacting commentary on the group and its philosophies. Never mind that Anderson himself kept insisting it is not about Scientology. Wink, wink. Got it. Not Scientology. But some other group that looks an awful lot like it.

It’s hard to take Anderson’s claim at face value when also reading in the press that he reported showing the film to Tom Cruise and they are still friends. If it’s not about Scientology, why is friendship with Tom Cruise at stake in the showing of it? But, wait a minute – If friendship with Tom Cruise is at stake in the showing of it, how could it possibly be a critique?

Here’s the “critique” I got from my second viewing of the film: Actually, Scientology is not so bad. Of course, recent articles in The New Yorker and Vanity Fair beg to differ. In fact, there is a considerable gap between those disturbing portraits and the picture Anderson paints for us. Possibly, the most difficult truth to face for Anderson fans is that, by the time it got to the screen, The Master had been stripped of all intention to put Scientology on the hot seat. If Anderson did initially plan on applying critical thinking skills to the bizarre belief systems and hurtful practices of a religious subculture, in the end he backed away from it.

So, assuming The Master is not about Scientology, as Anderson claims and I am now willing to believe, what is it about?

Anderson reports getting the footage into the  editing room and discovering that the film is about “two guys just desperate for each other, but doomed. Sadly doomed.” So the film is about the father/son relationship between the Master and Freddy. Indeed, the film begins with Freddy, the broken war veteran, literally, getting on board with the charismatic cult leader. The Master regards Freddy, at first, as a wild animal to tame and, then, as the unquestioning son he wishes he had. The film ends with Freddy making a final split from the Master and the group. But he is no longer the broken war veteran he once was. The “processing” has made him less volatile and unpredictable, as evidenced by the relative equanimity he exhibits when receiving news of his former love’s marriage to another man.

editing room and discovering that the film is about “two guys just desperate for each other, but doomed. Sadly doomed.” So the film is about the father/son relationship between the Master and Freddy. Indeed, the film begins with Freddy, the broken war veteran, literally, getting on board with the charismatic cult leader. The Master regards Freddy, at first, as a wild animal to tame and, then, as the unquestioning son he wishes he had. The film ends with Freddy making a final split from the Master and the group. But he is no longer the broken war veteran he once was. The “processing” has made him less volatile and unpredictable, as evidenced by the relative equanimity he exhibits when receiving news of his former love’s marriage to another man.

Although this qualifies as a character arc, it is strangely unsatisfying. One reason is that another result of keeping the viewer at a distance from the action is it gives the main character an Everyman quality. We are not in Freddy’s inner circle, intimately sharing his experience, so he comes across more as a generic traumatized war veteran than a complex individual we know well. And then there’s his passivity. As the old saying goes, it is through a man’s actions that we know him. But, despite his periodic uncontrolled outbursts, not much of Freddy’s circumstance is driven by his actions, until, very late in the story, when he gets on the Master’s motorcycle, drives off across the desert and doesn’t come back. So maybe that’s the point – that the real measure of Freddy’s growth within the cult is in his leaving it.

However, this is where Anderson’s watered-down treatment of his subject is particularly evident since a defining characteristic of a religious cult is all the effort put into preventing people from leaving. It shouldn’t have been that easy for Freddy. And, for those viewers looking forward to doing some serious thinking about the allure of cults and the fragilities of people who give themselves over to them, this lack of critical perspective leaves a void. Anderson tried to fill that void with a doomed father/son relationship story, but it left many viewers wanting.

Here’s my theory as to why — A doomed  father/son relationship is a feeling story, full of pathos and tragedy. Two men drawn to each other are ultimately unable to achieve a meaningful connection. The Master tries to control and manipulate the younger Freddy, who he is genuinely fond of, until Freddy gains enough self-control to claim autonomy and finally break away. But when we last see Freddy, he is on the beach, with the woman made of sand, letting us know that, despite all he has been through, he is still lonely. What is there to think about in that?

father/son relationship is a feeling story, full of pathos and tragedy. Two men drawn to each other are ultimately unable to achieve a meaningful connection. The Master tries to control and manipulate the younger Freddy, who he is genuinely fond of, until Freddy gains enough self-control to claim autonomy and finally break away. But when we last see Freddy, he is on the beach, with the woman made of sand, letting us know that, despite all he has been through, he is still lonely. What is there to think about in that?

While Anderson keeps us at a distance from the story to enable us to think, he doesn’t give us a critical perspective to think about. What he gives instead is a poignant story of human disconnection and loneliness. But he doesn’t bring us close enough to the characters that we may genuinely feel their loss.

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………

You can watch The Master on the following Video On Demand websites:

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………