Blog

We Are the 40%!

Posted by Jennine Lanouette on Tuesday, June 25th, 2013

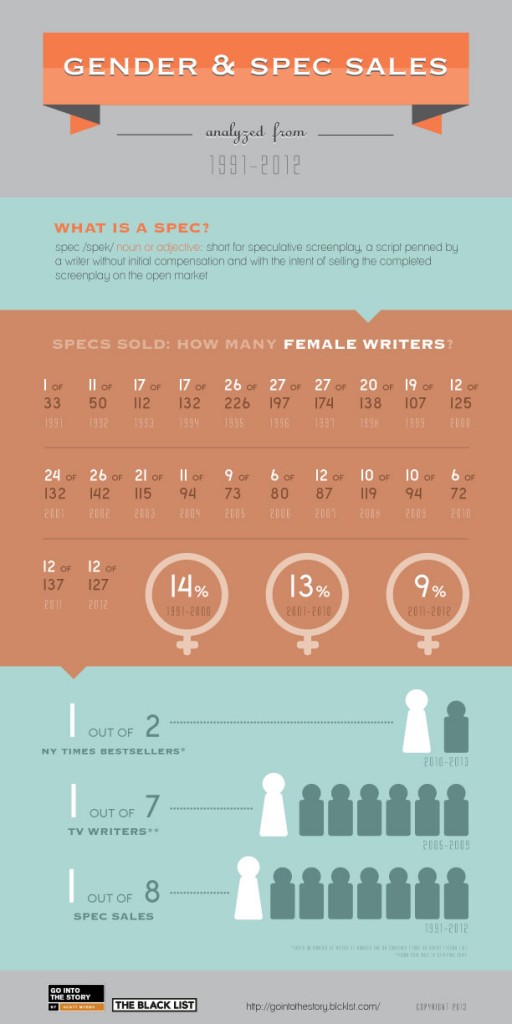

Last week, a chart appeared on the popular screenwriting website Go Into the Story analyzing gender inequity among spec script sales in the American entertainment business. The figures not only show a stark disparity between the sexes but also a steady decline in spec sales among women from 14% in the 1990’s to 9% for 2011 to 2012. The research is credited to  Susana Orozco. But in his accompanying commentary, Scott Myers asks, first, if this problem is systemic and, then, if this means there are fewer women interested in screenwriting.

Susana Orozco. But in his accompanying commentary, Scott Myers asks, first, if this problem is systemic and, then, if this means there are fewer women interested in screenwriting.

In the very next sentence, Myers himself puts forth a couple of statistics that begin to shed light on his questions. In 2013, nearly 30% of Nicholl Fellowship applicants were women (screenwriting contests being, by definition, entirely spec scripts) against 13% of spec script sales in the preceding years of 1991 to 2012. Taking the Nicholl Fellowships as a representative sample (lacking any other such sample), it appears that, although fewer women than men are writing scripts, far fewer women are getting sales. And the number is going down. Thus, the question that needs to be asked is not about women’s interest level.

In the comments section following, British screenwriter Lydia Mulvey sheds further light by pointing out that, when looking at Nicholls results, “the number of women who receive a fellowship is about the same ratio (give or take) as the number of female entrants.” In other words, when women’s screenplays are read gender-blind, their success is in direct proportion to their participation. So the question to ask is: Why and how is it that women continue to be discriminated against in this industry despite their efforts to push through all the barriers? And I have a follow-up question: Why are people so reluctant to ask this question?

In a piece posted on No Film School speculating on the significance of these figures, V Renee does pose the apparently dreaded question of sexism. But then she wonders, alternatively, if perhaps women are just not writing what’s being bought. (If only women would write what Hollywood wants to buy, then at least we could get our numbers up.) Finally, like Myers, she lands on what I suppose is the more comforting possibility, that there are simply not very many female screenwriters, which, presumably, would be no one’s fault.

There is no disputing that fewer women decide to be screenwriters than men. Having taught screenwriting for over 20 years, I would put the ratio, observed in my classes, at roughly 60% to 40%. I prefer to view this not as women staying away (in my experience, they show up with great energy and commitment) but rather as men over-favoring it among forms of writing. For men (as a whole), action-oriented screenwriting may have more natural appeal than a more introspective form of writing, like, say, poetry.

Given this action slant, men are currently benefitting from the action-obsessed culture of the American film industry. This is one of the ways in which those 40% of screenwriters who happen to be women are losing out.

Still seeking solace for this dismal state of affairs, Renee cites her screenwriting professor’s insistence that a studio will rarely turn away from a great story. Putting aside the implication here that maybe the problem is simply a lack of greatness among women’s screenplays, this claim begs the question: Great story according to whose definition? (Please see above comment re: action-obsessed film culture.)

Maybe some related statistics can help broaden the picture. Despite that, in my estimation, roughly 40% of screenwriters are women, from among the 250 top-grossing films in 2010:

16% of the protagonists were female,

10% of the writers were female,

7% of directors were female.

These figures come from a documentary on women in the media, made in 2011 by Jennifer Siebel Newsom, aptly titled Miss Representation. The film also counts female film industry executives “with any kind of clout” at 3%, showing that the further up you go in the power echelons, the less influence women have. The figures presented by Orozco show that, in 2010, women came in at 8.3% of spec sales, consistent with the pattern. And when determining whether a phenomenon is systemic, the first thing you want to look for is a pattern.

According to Siebel Newsom, when it comes to discrimination against women in film and television, no single aspect of the industry can be fully understood without taking in the whole picture. Through analysis of media images and interviews with experts, she demonstrates that misrepresentation of women both in front of and behind the camera is deliberate and calculated. The mainstream media has two objectives: one, to pose women’s worth entirely as a measure of physical appearance; and, two, to abuse, discredit and thwart the efforts of any woman in a position of power or leadership. This second objective appears to be paying off quite well since the U.S. is way down the list of industrialized nations when it comes to female representation in elected positions.

According to Siebel Newsom, when it comes to discrimination against women in film and television, no single aspect of the industry can be fully understood without taking in the whole picture. Through analysis of media images and interviews with experts, she demonstrates that misrepresentation of women both in front of and behind the camera is deliberate and calculated. The mainstream media has two objectives: one, to pose women’s worth entirely as a measure of physical appearance; and, two, to abuse, discredit and thwart the efforts of any woman in a position of power or leadership. This second objective appears to be paying off quite well since the U.S. is way down the list of industrialized nations when it comes to female representation in elected positions.

This is an issue that goes beyond being simply a grievance about equal rights for women, equal opportunity, equal pay, etc. It is a crisis for humanity. It is well known by now among reasonably informed people that the world has devolved to a place of tremendous imbalance in the economic, humanitarian and environmental spheres. Siebel Newsom’s film shows that gender imbalance is a crucial ingredient for maintaining all other imbalances. If we want more balance in the world, we must begin with balanced gender representation. The first step to achieving this is to take off our blinders about the extent and cause of sexism in our industry.

But don’t take my word for it. See the film: www.missrepresentation.org.